History of Asian Martial Arts

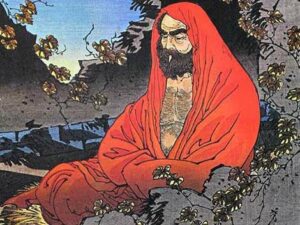

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma: Origins and Arrival at Shaolin Temple

The sensational development of Asian martial arts occurred thanks to the fusion of the principles of Indian Buddhism and Chinese Taoism.

Among all the legends surrounding the origin of Asian martial arts, that of the monk Bodhidharma (India, ~483-536) and the Shaolin Temple is certainly one of the most fascinating and widely supported.

Bodhidharma (Ta-Mo in Chinese, Daruma in Japanese), whose life falls between the 5th and 6th centuries AD, is one of the most enigmatic figures. Legends about him are numerous, but verifiable historical sources are scarce. Among the few certain facts is his origin: he came from a noble family in southern India.

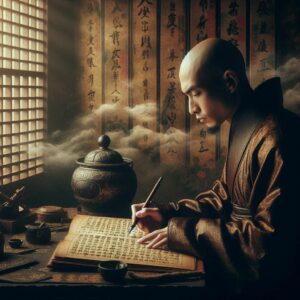

During his time, Bodhidharma did not attract much attention from the Chinese people; in fact, the first records mentioning him date back a hundred years later. Our knowledge of his life comes from two sources.

- The first, which contains the oldest information about him, mentioning him only as a monk dedicated to meditation, consists of the “Biographies of the Great Priests”, a book composed by Tao-Hsuan at the beginning of the Tang dynasty, around 645. The author was the learned founder of the Vinaya sect in China, but he lived before Chan Buddhism reached its maturity with the sixth patriarch Hui-neng, who was nine years old when Tao-Hsuan wrote the “Biographies”.

The other source is the “Annals of the Transmission of the Lamp” (Chuan-Deng-Lu), compiled by the Chan monk Tao-Yuan in 1004, at the beginning of the Song dynasty, after Chan had been formally recognized as a special current of Buddhism. The work contains sayings of Chan masters and news about their activities. The author often invokes the authority of certain previous Chan stories, which have been lost, so much so that if they only know the titles.

Bodhidharma, whose original name was Bodhitara, was a prince originally from Kancipura (Xing-Chi), a small but prosperous Buddhist province south of Chennai (Madras), third son of King Sugandha, ruler of the Syandria dynasty, a small kingdom in the province of Madras in southern India. Another certain fact is his lineage, that of the XXVIII Patriarch of Buddhism, therefore a direct descendant of Siddhartha Gautama Buddha. But, despite being the successor of the historical Buddha, it is difficult to imagine two more different characters. Born in a period of turmoil, when India was devastated by the Huns from the North, as a royal member of Kshatriya, Bodhidharma received a military education, in the Vedic martial art, then called Kalari-Payat, and the training necessary to one day succeed his father to the throne; it was this that brought him into contact with Buddhism.

Tradition has it that, around 527 AD, Bodhidharma undertook a journey from his native land to China to spread Buddhism. Probably Bodhidharma’s mission in China was to assist or succeed his famous contemporary Bodhiruci. Thus Bodhidharma embarked and, after three years of difficult sea voyage, landed in Canton (Guangzhou) in China, where he was received by Emperor Liang Wu Di, of the Liang dynasty.

Driven away from the court because of his innovative thinking, Bodhidharma continued his journey to the foot of Mount Songshan in Henan province, reaching the Shaolin Temple (Shorinji in Japanese, Sorimsa in Korean). It was said he crossed the Yangtze River on a reed.

He spent nine years meditating in a cave in Wuru Peak and began the Chinese Chan tradition at the Shaolin Temple. He was later honored as the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism. According to legend, this will be the starting point for the birth and development of modern Asian martial arts.

Shaolinquan and the Development of Martial Arts in China

Here he founded a school based on meditation: Dhyana in Sanskrit, Chan in Chinese, Zen in Japanese. Given the poor physical condition of the monks, he taught them breathing exercises and gymnastics and, according to legend, also unarmed combat techniques, which over time were enriched and perfected under the generic name of wushu, or martial arts (bujutsu in Japanese). According to many masters, the first true martial art of the East was that practiced in the monastery, called shaolinquan, whose original form has been lost but has been reconstructed on the basis of the derived styles.

The many styles of wushu have developed along two main lines:

- The first is called Weijia and includes the “external” or “hard” fighting styles, which are based on the use of straight-line force, developing vigorous movements such as kicks and punches, and seem to be directly inspired by the original school of the Buddhist temple of Shaolin. Among these was the art of shorin-ryu, which later evolved into shuri-te on the island of Okinawa, from which karate derives, spread in Japan by Gichin Funakoshi (1868-1957).

The second direction is Neijia and includes the “internal” or “soft” styles that were headed by the Taoist temple of Wutang, which develop with the concept of Wu-wei, usually translated as “non-action,” but would be better to say “non-interference”: it represents the ability to dominate circumstances without opposing them, even managing to defeat an opponent by apparently yielding to his assault to neutralize him with circular movements and turn his own force against him, favoring ventral breathing, similar to that of Indian yoga. The soft styles led in China to the development of disciplines such as taijiquan, still studied today especially for the psychophysical health of the practitioner, while in Japan they generated jujutsu, from which judo by Jigoro Kano (1860-1938) and aikido by Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969) derive.

Obviously, Taoist philosophy provides for a complementarity of Yin and Yang principles (passive and active), so it is unlikely to find a technique that develops only “hard” or only “soft” movements. All Chinese schools seek a development of Chi, the inner energy, only that, to realize it, they choose different paths.

Subsequently to Bodhidharma’s visit, who presumably then left to continue his work of “evangelization”, the Shaolin monks continued to practice both yoga and martial arts and the following century already enjoyed the reputation of being invincible, capable of defending themselves effectively against bandits and criminals who took refuge in the woods.

Years of training, isolated from the world, transformed the monks into formidable fighters, which is why they became famous throughout China, and their superiority was not only physical, but thanks to Chan Buddhism, also spiritual and mental.

Modern historians, however, exclude that Bodhidharma taught his disciples combat techniques and indeed even question their existence. Scholars believe that these indications from traditional sources are legendary. According to Bernard Faure, when Hongren’s disciple (601-674), Faru (638-689), settled in the Shaolin temple in 686, he spread the doctrines of the Damozong school (original name of Chan Buddhism) and a synthesis was created on the figures of Bodhidharma, Fotuo and Sengchou.

What has been historically ascertained, however, is the presence, in this temple, of the Indian monk and translator of texts from Sanskrit to Chinese Bodhiruci (?-527).

Regardless of whether or not Bodhidharma existed, it seems certain that, around 500 AD, some Indian monks introduced a particular form of Buddhism, called Chan, which would later influence the entire martial philosophy of the Far East. Certainly we can say that in India a martial form had already been practiced for centuries which, in the technique known to us today, has significant analogies with the styles of the Shaolin tradition.

As mentioned, from the period following Bodhidharma, martial arts began to flourish throughout Asia, and this will be our starting point to try to outline, in the next articles, a picture of the history of martial arts in individual countries.