History of Capoeira

From the quilombos to the first academies

Premise

The history of capoeira, one of the highest artistic expressions of Brazil, is very complex and difficult to trace due to the lack of written sources and the uncertainty among scholars, due to the fact that after the abolition of slavery in Brazil, all documents related to this practice were destroyed on December 15, 1890 by the Counselor Ruy Barbosa while he was Minister of Finance in the discretionary government of General Deodoro da Fonseca, with the intent of leaving as little information as possible about this period. To indicate capoeira as a Brazilian martial art only partially defines the peculiarity of this discipline, a fight that originates from the mixture of fighting and dance rituals of the local Indians and African tribes captured and deported to Brazil by the Portuguese through their colonies.

The colonization of Brazil and the beginning of slavery

On April 22, 1500, Pedro Alvares Cabral landed in Brazil, and with him began the history of Portuguese colonialism. To solve the problem of slave labor, the colonizers began to capture Africans (physically stronger than the native Indians, decimated by the diseases brought by the colonizers). During the period of the slave trade, it is estimated that more than two million people were deported to Brazil from Africa. There were two large groups of African tribes that arrived in Brazil; identified by linguistic strain, they are: Sudanese and Bantu. The Sudanese came mainly from the Gulf of Guinea, in West Africa. The most important, both for the greater quantity and for their culture, were the Nago or Yoruba from Nigeria and the Gege (Ewe), from Dahomey (today the Republic of Benin), who formed a black religious order in Brazil called Gege-Nago. The Bantu came from Congo, Angola, and Mozambique (East Africa). The tendency of Africanist historians seems to be to think that the first blacks who arrived in Brazil came from Angola.

The slaves were distributed to the three main Brazilian ports: Bahia, Recife, and Rio de Janeiro, and then exploited in backbreaking work on plantations (sugarcane, tobacco, coffee, etc.) for many hours a day, then retiring to the “Sem-alas”, large and miserable underground dormitories, dark and without walls (sem = without, ala = side of wall) dividing walls, living in terrible conditions. It is evident that the slaves had as their only aspiration to escape. Taking advantage of the confusion generated by the Dutch who invaded northeastern Brazil in 1630, thousands of slaves fled the fazendas to hide in the virgin forest, gathering in villages that were called Quilombos, a name later given to this type of independent community. However, one should not think that only African blacks inhabited the Quilombos, in fact, even the Indians and even some Europeans who did not agree with the political and social choices of the regime at the time were part of it.

Quilombo dos Palmares

In Recife, a group of forty enslaved people rebelled against their masters, killing those who were not enslaved and burning down the plantation. They then declared themselves free and decided to find a place where they could remain safe and secure from slave hunters. They headed towards the mountains of Serra da Barriga and embarked on a journey that lasted several months, a feat made possible only with the help of their Indigenous friends. They managed to find an ideal location, which, due to the great abundance of palm trees, was named Palmares.

The Serra da Barriga hosted several quilombos, but the largest and most famous was always the first: Palmares, founded in 1610 and probably located in the northeastern state of Alagoas, transformed into a fortress, became famous for the valor of its inhabitants in the battles fought against those who wanted to destroy it and became a symbol of the struggle of slaves against their tormentors. In this place, the first community of free blacks in Brazil was born.

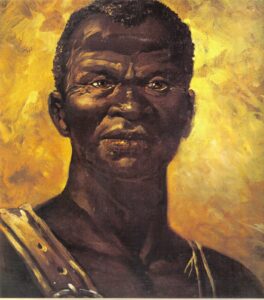

The village of Palmares survived for more than eighty years, resisting the onslaught of the Portuguese and the Dutch; it was destroyed in 1695 after a five-year siege involving 9,000 soldiers. The history of Quilombo dos Palmares is linked to the figure of Zumbi (the last king of Palmares).

Zumbi, in the Ewe/Fon language, means immortal, dead-alive. Palmares and Zumbi became not only a symbol for the black race but also a Brazilian symbol of resistance to domination and, consequently, of the most traditional capoeiristas.

According to some, capoeira, whose embryo had already been born on the plantations, was deepened and developed precisely in Palmares, from the union of African culture with that of the local Indians.

The few remaining documents, the first to speak of capoeira, date back to 1624 and are the diaries of the expedition leaders tasked with capturing and bringing back the black slaves who tried to escape. These documents describe a strange way of fighting among the slaves that appeared very effective to the European expedition leaders: “Using kicks and headbutts as if they were real untamed animals.”

The widespread myth is that capoeira was a way for slaves to train to fight while disguising the fight with dance, characterized by expressive elements such as music and harmony of movement. This may only be true for a very primitive stage of its development, because in reality, the practice of capoeira was banned for slaves from 1814, along with other forms of cultural expression, primarily to prevent their aggregation, although some sources say that this form of martial art continued to exist and develop considering that it has survived to this day.

The End of Slavery and the Evolution of Capoeira

Brazil gained independence from Portugal in 1822, becoming an empire, but slavery persisted for nearly fifty more years. It wasn’t until 1871 that the emancipation of the children born to enslaved people was decreed. Through subsequent legislative acts, slavery was finally abolished. The final decree, known as the “Lei Áurea” (Golden Law) and promoted by Princess Isabel, was signed in 1888. The following year, a military coup marked the end of the Empire and established the Republic.

With the abolition of slavery, some former slaves returned to Africa, but the majority remained in Brazil. This mass of ex-slaves headed for the large cities; however, not all managed to find work and a home (previously, enslaved people all lived together in “Sem-alas” within the plantations).

They settled in the vicinity of the cities, creating the first slums, and were unable to easily integrate into the socio-economic fabric.

Especially in large cities, many of them turned to crime to survive, often resorting to capoeira in clashes with other criminals or with the police. In fact, capoeira gangs were at the forefront of riots and disturbances. Capoeira was therefore soon associated with crime and street delinquency, so much so that it was banned nationwide as early as 1892. The practice of capoeira remained clandestine (hence the use of a nickname, a nickname, for each capoeirista), often violent and practiced only on the streets by disreputable individuals, listed by the police as capoeiristas. The capoeira (capoeirista) was easily distinguished by his way of dressing and his attitude. Melo Morais Junior described the capoeira of Rio de Janeiro as follows: “Wide trousers, unbuttoned sack coat, colored shirt, cloth tie with a sliding ring, belt-like bodice, narrow-toed shoes, felt hat. His gait is loose and swaying and in conversation with companions or strangers he keeps his distance, as if he were always on the defensive.” The felt hat could become, in the absence of weapons, a means of defense (crushed lengthwise). Capoeeiras also used sticks or razor blades held between the big toe and the first finger, becoming a very dangerous weapon.

Before the first schools (Academias) began to form at the beginning of the 20th century, the meeting points for capoeiras were places-neighborhoods where the stevedores waited for work. In Bahia, almost all slaves after liberation, not liking the field work they already did, lived from day to day (ganhadores). It seems that great capoeiristas belonged to them. These meeting points were called “canto” – literally corner -, each canto had a leader called “capitão” in Bahia while in Recife the groups had the name of “companhias” and the leader of “governador” (Kay Shaffer).

The measures adopted by the police until the beginning of the current century to suppress them proved ineffective and just when the situation was becoming increasingly tense, Brazil went to war with Paraguay (1865-1869) marking the end of their violence: to eliminate them, in fact, the Government of Bahia sent a good number of capoeiras to fight, many of their own free will and many others forced, but the black militia sent to the front returned victorious and its members became national heroes. Capoeira entered another phase of its history.

Legalization and the Birth of the First Academies (Academias)

In 1934, President/dictator Getúlio Vargas legalized various Afro-Brazilian cultural expressions that had been previously banned, such as Candomblé and capoeira, on the condition that they be practiced in closed spaces. Until then, capoeira had been practiced as a “folkloric dance” in hidden places, which often coincided with terreiros (places where the Umbanda and Candomblé religions were practiced), where capoeiristas did their best to keep the tradition alive.

Getúlio Vargas’ move was clearly an attempt to control what was, in fact, happening clandestinely. However, there is no doubt that, while this event forced capoeira to come to terms with power, it also allowed it to expand unprecedentedly.

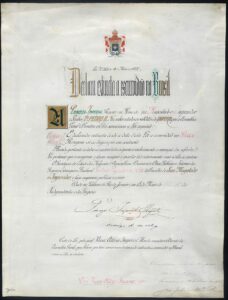

In 1937, Manoel dos Reis Machado, known as Mestre Bimba (1899-1974), one of the most important capoeira masters, received an invitation from the president to give a demonstration in the capital. After the successful presentation, he returned home to Salvador de Bahia with the government’s permission to open the first official capoeira academy in Brazil, which had already been operating clandestinely since at least 1932.

This was the first step towards a more open development, and finally, the sport was redeemed and began its slow ascent.

Mestre Bimba called his style “Luta Regional Bahiana” (Bahian Regional Fight), and even when he later used the simpler term “capoeira Regional”, he always wanted to distinguish his discipline from what he called “capuera pra turista ver” (capoeira for tourists to see), which he believed had lost all its martial characteristics.

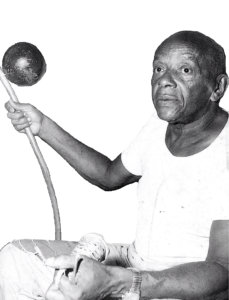

Contemporaneously with Mestre Bimba, numerous other capoeiristas such as Waldemar, Canjiquinha, Cobrinha Verde, and Leopoldinha tried to organize the practice and teaching of capoeira. In particular, Vicente Joaquim Ferreira Pastinha, known as Mestre Pastinha (1889-1980), undertook the teaching of capoeira, emphasizing its cultural and historical value. Mestre Pastinha assumed the role of guardian of traditional capoeira, which, in opposition to Mestre Bimba’s Regional style, was called capoeira Angola. His Centro de Capoeira Angola, opened in Largo do Pelourinho in 1941, thus became an important reference point for the revaluation of the Afro-Brazilian heritage of capoeira.

From the 1950s onwards, a “sporting” trend of capoeira developed, based on an increasingly rigid division into groups and academies. Although very different from Mestre Bimba’s original art, this capoeira is still often called Regional or contemporary.

As a reaction to this phenomenon, capoeira Angola regained popularity from the 1970s onwards. Although it refers directly and constantly to Mestre Pastinha’s capoeira, this “current” is also the protagonist of an evolution, albeit with constant reference to tradition.

In 1974, capoeira was recognized as a Brazilian national sport.

Despite the great contribution he made to what is the second national sport in Brazil after football, Mestre Bimba died in poverty on February 5, 1974.

Mestre Pastinha worked a series of humble jobs all his life, such as a shoeshine boy. He was a tailor, a supervisor in a gambling house, and a dockworker, just so he could continue to be essentially an angoleiro. With the worsening of his health, his school fell into disrepair. He suffered a cerebral edema in 1979. Old, sick, and almost blind, he was asked by the authorities to leave the premises so that they could be fixed. But the spaces were never returned to him. He played his last roda at the age of 92, on April 12, 1981, and died a few months later, abandoned in a municipal hospice. His most loyal students and considered his direct descendants are João Grande and João Pequeno.

Capoeira in Italy

At the end of 1979, Mestre Canela left Brazil for Europe together with Mestre Zè-Maria and other artists of Brazilian art and culture. In 1980, while touring Europe, he did not find any capoeira groups and, in order to maintain his physical condition and training, he decided to confront the realities of martial arts practiced in various nations by participating in karate, kung-fu, and full-contact matches. In 1982, once he had settled in Viterbo, as a good omen for the dissemination of capoeira in Italy, he formed a group to which he gave the same name as his first group founded in Rio de Janeiro ten years earlier: thus, the capoeira Mangangà group was born in Viterbo.

Conclusion

On November 26, 2014, the Capoeira Roda was inscribed by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. UNESCO has recognized capoeira as a celebration born from resistance against all forms of oppression. The roda is a ritual space that provides a sense of companionship and identity for a community that is constantly expanding in Brazil and elsewhere. The idea is that capoeira should become a means of resistance and promote dialogue between different ethnic groups, social classes, and nationalities.